A practical introduction to cryptography and steganography (Chapter 1)

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

This document is meant as an introduction for whoever wishes to explore the concepts behind cryptography and steganography.

In the Cryptography and Steganography sections, I will try to expose the basic concepts behind each of the diciplines.

In the Implementation section, I will briefly touch upon certain subtleties but the gist of it is in the video and the code.

You will also find links to books, articles, videos, etc. in the References section.

2 Cryptography

2.1 Introduction

Cryptography can be defined as the art/discipline or study of methods for secure communications. More specifically, the analysis and design of mathematical algorithms that allow for clear data to be rendered unintelligible. Though mathematics is a key element in this discipline, cryptography gathers a myriad of other fields: physics, electronics, computer science, … that combine together to provide solutions to the secure requirements of the different components of a communications channel.

Nowadays, cryptographic methods are deployed to secure and authenticate almost every electronic transaction that goes through the gargatuan connected network of devices on which relies modern 21st century life: the Internet. Phone communications, bank transactions, web browsers, networking protocols, … rely heavily on standardized cryptographic algorithms and equipment that allow for a certain level of confidentiality and act as a deterrent for whoever whises to eavesdrop on a communications channel.

Cryptography is a field in constant evolution. In form and in content. Many references are available on the web so you can try to wrap your intellect around the enormous wealth of notions and concepts that make up this discipline. Every cryptographic problem is multi-faceted and requires solid notions in mathematics, software engineering and hardware architecture. This said, I would recommend any individual wishing to dive deep into the world of cryptography to broaden their spectrum of knowledge and to try to adopt a systemic approach.

Have fun :)

2.2 Symmetric algorithms

Symmetric algorithms define a class of encryption methods in which the same key is used for encryption and decryption (symmetry). These algorithms require the key to be kept secret in order to maintain a high level of security. Symmetric algorithms include AES, Blowfish, Twofish, Chacha20, … These algorithms are usually designed for high performance and are either implemented in code (i.e. openSSL) or in hardware (cryptographic chips or crypto-processors).

The main issue with symmetric encryption/decryption algorithms is the key exchange (shared secret). Securely exchanging cryptographic keys between two or multiple parties requires a reliable and safe communications channel. A solution to this problem is asymmetric algorithms.

2.2.1 Stream vs block ciphers

Stream and block ciphers are methods used to convert a clear input text into an encrypted output and belong to the class of symmetric ciphers.

- Stream ciphers

A cryptographic algorithm is considered a stream cipher if the basic encryption and decryption operations are applied to a byte (or text character). Encryption, or decryption, is therefore applied one byte at a time.

Here is an example of a stream cipher innermost loop performing a XOR operation between each byte of a clear text (in) and a key (key), and stores the result in an output buffer (out). This algorithm is sometimes referred to as OTP (One-time-pad) or as the Vernam Cipher.

for (i = 0; i < strlen(in); i++) out[i] = in[i] ^ key[i];

This algorithm has been proven by Claude Shannon (the father of Information Theory) to be the most mathematically secure if used under certain conditions:

- The key must be truly random

- The key must be at least as long as the clear text

- The key must never be totally or partially reused

- The key must be kept secret

When these conditions are respected, this algorithm can ensure "perfect secrecy" because no information about the clear text (except its length) can be extracted from the encrypted text.

- Block ciphers

Contrary to stream ciphers, block ciphers apply invertible transformations on blocks of bytes rather than on single bytes. These algorithms rely mostly on substitution-permutation networks such as Feistel, or Lai-Massey networks.

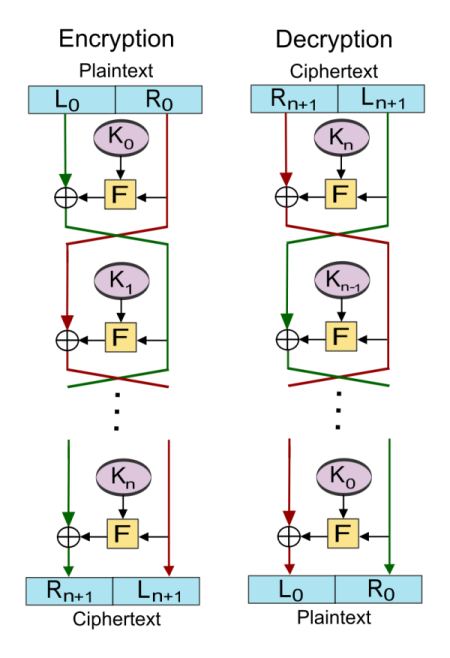

Figure 1: Feistel scheme (source Wikipedia)

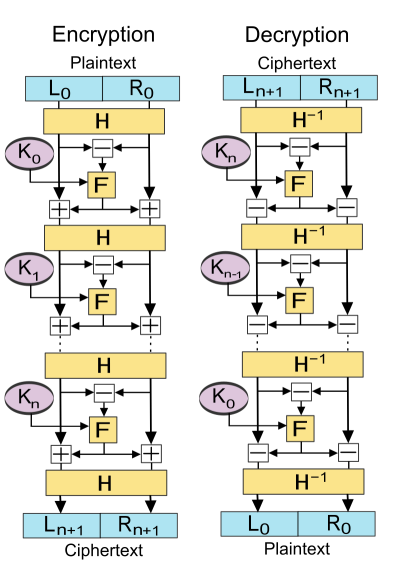

Figure 2: Lai-Massey scheme (source Wikipedia)

2.3 Asymmetric cryptography

Asymmetric cryptography or public-key cryptography is a scheme based on the use of a pair of keys (public key, private key) to secure an exchange. The public key is known to the outside world and is used to encrypt data destined to the owner of the key. The owner, and only the owner, can then use the secret private key to decrypt the encrypted text.

This scheme allows for higher security because no secret information or prior knowledge is shared between the communicating parties and because sender authentication can also be applied (non-repudiability).

The security of asymmetric algorithms is usually based on mathematical concepts that render any code breaking endeavor impractical. For example, the RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) algorithm relies on the fact that no modern computer system can factor a VERY large integer (n) into two large prime factors (n = p x q). Another algorithm, ElGamal, relies on the difficulty to compute discrete logarithms of certain problems in a given cyclic group (i.e. a multiplicative group of integers modulo n).

One of the main advantages of public-key cryptography is the ability to apply sender authentication and to exchange keys in a safe manner. The Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol is one of the earliest methods presented to tackle the key exchange problem and is still largely used today.

2.4 Hashing algorithms

Hashing algorithms are one way functions (bijections) that scramble the input data into a unique signature. This signature, also called a hash or a digest, is irreversible and contains no information on the source data. Hashing functions are usually used to verify the integrity of data and generate authentication signatures. Hash algorithms are usually implemented using a mix of bitwise logic (xor, and, or, shifts, rotations, …) and arithmetic operations, and are usually designed for performance.

For example, login credentials are almost never stored in clear form in authentication databases and only their hash is stored. When a user tries to log in, the authentication interface captures the clear login credentials, hashes them, and sends the hashes through the network to the authentication server that verifies the received hashes against the ones stored in the login database. This way, if a security breach occurs, the data remains unintelligible and almost impossible to reverse into clear form.

Another use case of hashing functions is file integrity verification during download/upload. Many file transfer tools use hashing to ensure that the transferred files match exactly the source files. These tools usually start by calculating the hash of the source file which is then transferred to the destination end of the communications channel. After finalizing the transfer of the file bytes, the destination will recalculate the hash of the received byte stream and compare it to the previously received hash. If both hashes match, the transfer will be considered complete and the data valid. Otherwise, a transfer failure error will be raised.

There are many hashing algorithms available: MD5, SHA1, SHA256, RIPEMD, … providing different signature lengths and scrambling schemes. Some of these algorithms (namely MD5, SHA1) are known to have collision issues and should not be used anymore. A collision occurs when a hash function produces the same signature for two different inputs.

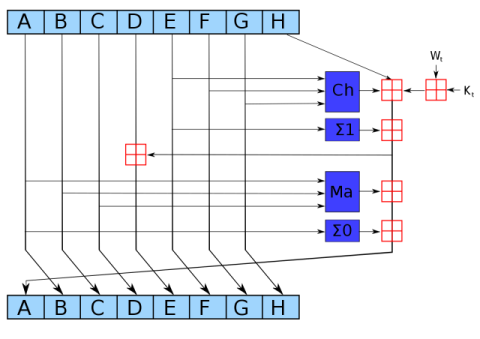

Below you can see an example diagram of how the RIPEMD-160 algorithm and the SHA2 family of algorithms compress blocks of data. The RIPEMD160 algorithm is used in addition to SHA256 to hash the public key in the Bitcoin protocol. The SHA256 algorithm is also used in the proof of work function of the Bitcoin mining algorithm as well as in the digital signature scheme.

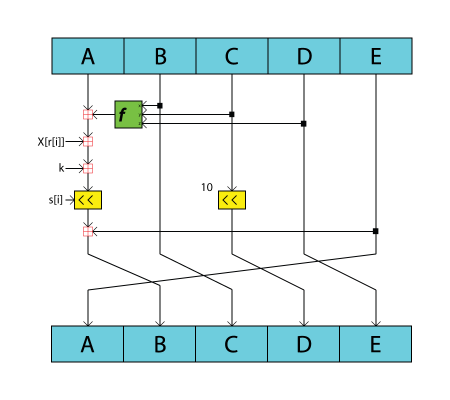

Figure 3: RIPEMD-160 compression function (source Wikipedia)

Figure 4: SHA2 compression function (source Wikipedia)

2.5 Random number generators

Random numbers are centric to many fields: Monte-Carlo computer simulations, statistical sampling, … and there are many methods/algorithms for generating random sequences. In general algorithms generate what is called pseudo-random numbers. These number sequences exhibit a certain entropy but can be regenerated if the system's initial state/seed is known. This reproducibility property is often used to generate the same sequence on two different computer systems that share the same seed.

On the other hand, true random numbers are usually generated by exploiting the random nature of a physical phenomena: thermal noise, electromagnetic noise, atmospheric noise, … The main issue with true random numbers generators is speed. The fact that they rely on a true source of entropy limits their performance to the speed of occurence of the physical phenomena.

Today, true random numbers generators come in multiple form factors (i.e. USB thumb drives, PCI card, …). For example, the Free Software Foundation offers a 50$ 32-bit True RNG https://shop.fsf.org/storage-devices/neug-usb-true-random-number-generator

Figure 5: A PCI true RNG from Sun Microsystems for SSL acceleration (source Wikipedia)

Under Linux, two devices are available for random numbers generation:

- /dev/random

- /dev/urandom

You can test their speed and create files with random byte values by using the following commands:

#Create a file with 200 random bytes using /dev/random $ dd if=/dev/random of=output.rnd bs=200 count=1 #Create a file with 1MiB of random bytes using /dev/random $ dd if=/dev/urandom of=uoutput.rnd bs=1024 count=1024

3 Steganography

3.1 Introduction

Steganography is the art/discipline of hiding data within data (or a message within another message). For example, hiding a file within an image, or a sound file within another sound file. The core principle behind staganography is concealment. This technique does not ensure the security of the concealed data, that's why it is always coupled with a cryptographic scheme that scrambles the data before they are inserted into the receiving file.

Steganography can be implemented in many ways, but I will only cover how to conceal bytes within an image. This technique relies on the fact that the human eye cannot catch subtle changes of colors in images with a high pixel density.

To make things clearer, I will introduce the PPM image format that uses a simple RGB encoding to represent image pixels.

3.2 The PPM format

PPM (Portable Pixel Map), is an image format that describes the components of an image using the structure shown below.

P? WIDTH HEIGH THRESHOLD PIXELMAP

In this format, each pixel is represented using three color components each encoded using a byte: R (red), G (green), and B (blue). The value of each color channel constitutes the weight/intensity of the color in question within the final observed color. For example, the RGB encoding for the color pink is: R = 255, G = 192, B = 203.

The first line of a PPM file contains the format identifier:

- P3 for an ASCII pixel map:

P3 3 2 255 255 0 0 0 255 0 0 0 255 255 255 0 255 255 255 0 0 0

- P6 for a binary pixel map stored as 1D array. In the example below the {} denotes a byte stream where FF is the hex value for 255.

P3

3 2

255

{ FF000000FF000000FFFFFF00FFFFFF000000 }

The second line contains the width and height of the pixel map. The pixel map is a 2D matrix of width columns and height rows.

The third line contains the color threshold. This value is used to limit the maximum value of a pixel color component.

The fourth line contains the pixel map.

3.3 Inserting and extracting bytes

Now that we know how the PPM format stores image pixels (3 bytes) we can easily devise a scheme that allows byte stream insertion.

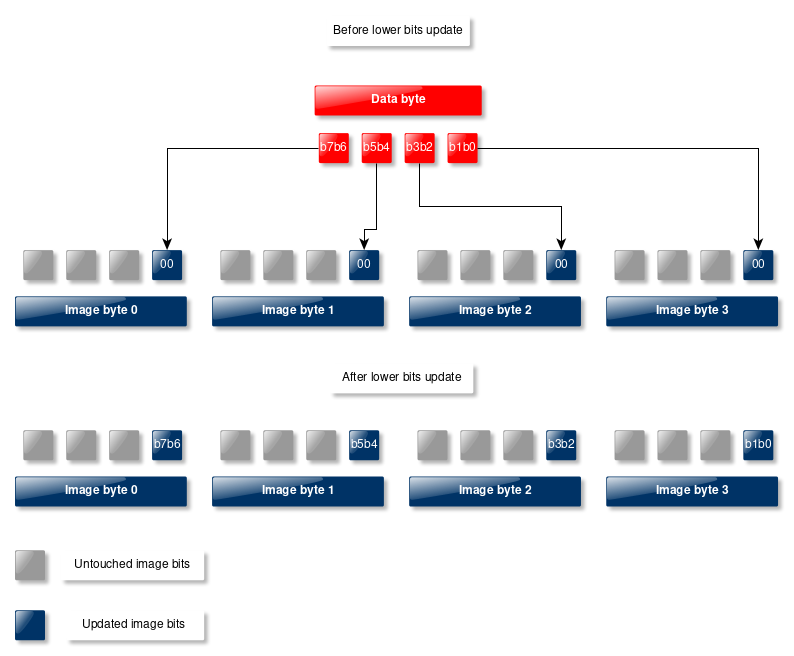

We know that the human eye cannot catch very subtle changes in color. What this implies is that we can change certain bits of the color components of a pixel without altering the overall appearance of the image. Given that each pixel is represented using three bytes, we will alter the lower two bits of each byte in order to avoid causing too much damage to the image quality. This means we are going to need four image bytes to store one data byte. This also means that we have to make sure that the target image file is at least four times larger than the data file we wish to insert.

Below is a diagram showcasing the insertion procedure.

Figure 6: Insertion of a data byte within four bytes of an image

In order to retrieve the inserted data we also have to insert the size of the byte stream. Otherwise, we won't be able to know how many bytes to extract from a given image. So, before inserting the data bytes, we will have to insert the 8 bytes that encode the byte stream size first. This will require 32 bytes of the input image. Once the size is inserted, we will insert the byte stream data starting at offset 32 of the input image. This means that we have to make sure the size of the image is at least 4 times the size of the data file + 8 bytes (for the data size).

3.4 Implementation

See the video :)

The tool I implement in the video performs a XOR encryption using a key file before inserting the encrypted byte stream into the target image. In the video you can see that I generated a random key of similar size to the test text file.

To paliate the size issue, compression (using zlib) can be performed after or before encryption to make sure we can use PPM files of relatively small sizes.

4 References

- Wikipedia is a good start (check the references at the end of the articles, they are usually more valuable than the articles themselves)

- https://www.schneier.com/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicada_3301

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Schneier

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhXCTbFnK8o

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aHkqB2-46k&list=PL6N5qY2nvvJE8X75VkXglSrVhLv1tVcfy

- RFC of the SHA family of hashes: https://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc4634.txt